|

Crows feet run from my eyes like rivulets down dusty hills. Gray strands of hair shoot across my head like lightning in a night sky. I’m aging. And I’ve accepted the way aging looks on me.

Acceptance is a powerful thing. I could stand before a Nordstrom mirror and declare the lighting is harsh, or I could accept the dimples dotting my thighs. I could scroll through photos of myself and conclude the angles were bad, or I could accept that that’s just how I look. I could dye my hair and inject Botox — and I very well might do that soon — or I could accept that I’m no longer 25. I could accept that beauty fades. And I could believe that youth is an attitude—a way of being and thinking—and that awe and wonder is what’s truly beautiful. I could choose to be grateful for every new wrinkle and strand of gray hair—for I am alive another day, joy etched into my face and wisdom painted onto my head. So many people don’t get to live long enough to see their body change, to see their children grow. Aging is a gift—a reminder that you have been given life, and your appearance reflects how fully you’ve lived it. Acceptance is a powerful thing. When we accept ourselves as we are, in every season of life, we see that aging is beautiful—that true beauty will never fade.

0 Comments

I used to be able to fly

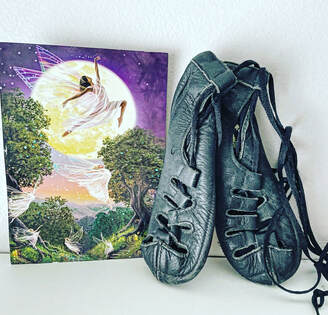

I danced upon moonbeams Leapt through the sky Butterflies, twists, promenades My legs gracefully glided Carrying me toward the stars To the sound of the bodhran Tin whistle and fiddle My spirit was free Time has slowed me down And my legs ache every night I see wrinkles etch into my skin Like frost on window glass My knees crack and my hips hurt I can’t fly like I used to Only in my dreams I used to be able to dance, light as a feather upon a spring breeze I can’t fly like I used to Only in my dreams And for now that’s good enough for me The Irish word seanchaí means “storyteller”or “barer of old lore.” In modern terms, seanchaí might refer to a “bullshitter.”

Both are true for my father, a man known for his gift of the gab. He’ll talk to anyone, and no subject is off limits. It helps he’s friendly looking, resembling some sort of mythical creature. His stories sound quite mythical, too. Like the true story of how he fell off a scaffold thirteen floors down an elevator shaft—on his face—and got up and walked away. Or how he shot himself in the foot with a nail gun and drove himself to the hospital. He’s fallen off of roofs, too. More than just a man with a history of construction trauma, he is a storyteller weaving together his own past with his rich Irish heritage. He grew up in a house with no running water; he bathed in a living room tub, made hot with boiled water from the fire. He used to roam the woods of Ireland barefoot—his childhood wild and free. He rode his bicycle up the town cathedral’s bell tower; jumped out from behind apples trees to scare oncoming nuns during afternoon prayer. A troublemaker. A hell raiser. A weaver of tall tales and star of true stories. But deep down, a sensitive soul interested in everyone’s stories, especially the underdog’s. He passionately roots for “the little guy” and believes in fighting against those who use their power for evil. You will always find him with a pint in hand, eyes sparkling, ready to engage in a political argument or retell a magical memory. Ready to knock his shoulder into yours after taking the piss out of ye. You’ll never quite know if he’s telling the truth or spinning a fable. But you’ll always know his stories will be entertaining and his intentions pure. For he is made of myth and magic. He is a survivor of unbelievable incidents. He is a modern day warrior. He is my father. He is the great seanchaí. “Daddy, are you dying?” my 2.5 year old daughter asked my husband after he let out a painful grunt. He was not aware she knew the word “dying.” “No, I’m just getting old. My back hurts,” he explained. “Ohh. You’re growing into baby,” she said, pleased with her conclusion. When my husband told me what she’d said, we laughed. But then I wondered: how did she connect pain and dying? And what did she know that we didn’t about “growing into a baby”? After my husband, daughter, her twin brother and I spent the past week in Florida visiting my husband’s grandfather in a memory care home, I realized my daughter was on to something. Pushing 91, her great-grandfather needs round-the-clock supervision and assistance with getting in and out beds, chairs, cars, going to the bathroom. His memory care home offers arts and crafts, and he and the twins sat side-by-side. He practiced holding the brush with his stroke-affected right hand; my twins practiced staying in the lines. He took a nap when they took nap, and they all went to bed at 8pm. Just like my children, Great Grandpa doesn’t have an appetite for dinner, but always for ice cream. Growing old IS like becoming a baby again. So where did my daughter’s wisdom come from? What if before we are conceived, our souls are waiting around in Heaven, hanging out with the souls who have already passed on? What if my children knew my great-grandparents because their souls had connected in the afterlife—which is also the “beforelife”? What if that’s how she knew? Maybe old souls coach the new souls as they enter tiny unborn bodies, encourage them as they are pushed out of the womb and into this bright, beautiful world. And maybe unborn souls welcome souls who recently passed into their arms, comforted like babies. I like to imagine my grandmother in Heaven holding my future grandchild, ready to encourage her when it’s her time to be born. I like to believe my wise daughter is right—we all grow back into babies. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed